Introduction

As Marcel Duchamp once noted: “Painting should not be exclusively visual or retinal. It must interest the gray [sic] matter; our appetite for intellectualization” (cited in Gray, 1969: 21). Indeed, fairs have historically been such means of stimulating the intellectualization of the global public and exhibiting art differently. In Michel Foucault’s terms, fairs represent “other spaces” (Foucault, 1984: 46-49) for the international circulation of ideas, technologies, and knowledge. The earliest state-sponsored fairs that included works of art appeared at the end of the 18th century. In their original configuration, they were related to the religious festivals and their accompanying markets. By the end of the 19th century, however, fairs turned into “exhausted institutions” freed from any other interest but the one of “expanding international economy” (Jones, 2016: 43). According to Walter Benjamin, fairs are responsible for producing subjects, symbols, and images of a “commodity universe” driven by the actors of capitalism: they “glorify the exchange value of the commodity”, and “create a framework in which its use value recedes into the background”, and “open a phantasmagoria which a person enters in order to be distracted” (1999: 7).

In the “commodity universe”, World’s Fairs are considered the “most spectacular, popular and important” event ever staged on a global scale. Since the First World’s Fair held in London in the Crystal Palace in 1851, these exhibitions have turned into the “encyclopedic” endeavors and “greatest gatherings of people in times of peace” that “have shaped the modern world and made that modernity manifest” (Jackson, 2008: 10). Since 1928, the organization of World’s Fairs has been a key responsibility of the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE), an international organization with its headquarters in Paris that regulates the frequency of World’s Fairs, as well as manages the rights and obligations of exhibitors and organizers.

Americans perceived the idea of a World’s Fair with great enthusiasm from the very beginning. In 1853, newspaper editor Horace Greely and showman P. T. Barnum mounted the New York Crystal Palace Exhibition that tried to imitate the 1851 World’s Fair in London. Greely and Barnum’s initiative was a disaster: the U.S. was soon torn apart by the Civil War and the public was not much interested in the event. With time, nevertheless, World’s Fairs became an unalienable part of the American cultural experience. Already back in 1876, the U.S. hosted the Philadelphia Fair that attracted 10 million visitors from all over the world and was the first international expo ever organized on the Northern American continent (Rydell et al., 2000).

During the Cold War, World’s Fairs were in the limelight of the ideological confrontation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. They had a clear objective to offer “a structured and planned view of the culture, values and aspirations of each exhibiting nation” (Masey and Morgan, 2008: 402). Since the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels, World’s Fairs were the central element of the Cultural Cold War. Apart from offering technological solutions to social, economic, and political problems, they also represented “the utopian potential associated with technology and consumerism” in the atomic age (Rydell et al., 2000: 137). At the same time, under the political circumstances of the Cold War, World’s Fairs per se turned into “cultural technologies that have nurtured—in roughly chronological sequence—nationalism, imperialism, and neoimperialism” (Rydell et al., 2000: 138). They became a symbolic battlefield in which “imagined communities” (Anderson, 2006) fought for the right to construct “national identities, selecting from among groups and subgroups those products and displays that served particular local, national, and international interests” (Raizman and Robey, 2020: 7).

The current paper examines the double-edged sword of exhibiting Andy Warhol’s Self-Portraits in the U.S. National Pavilion at the 1967 World’s Fair in Montreal, Canada. This particular case study is curious for several reasons. Primarily, the Montreal Fair was Warhol’s very first appearance on the international cultural scene under the auspices of the U.S. government. Andy Warhol (1928-1987), who is recognized today as America’s most expensive 20th-century artist (Artsy, 2013), struggled a lot to achieve recognition from the U.S. political establishment. Since Pop Art could never be explicitly defined as highbrow art, Warhol, as one of the “add-mass scene” (Amaya, 1965: 11) artists whose “stroke of genius was to have projected the machine in terms of ambiguity” (Calas and Calas, 1971: 116), could not enjoy large support on the part of the U.S. government for quite a long time. As art historian Sara Doris writes, “It was precisely the instantaneity of pop’s success that disturbed many critics: the art world seemed to be losing its rarefied isolation, succumbing to the faddish whims of consumer society” (Doris, 2007: 107). Warhol’s devotion to the vernacular products of the 1960s American mass culture contradicted “the European model of the struggling avant-garde artist” endorsed a decade earlier by Abstract Expressionist painters (Fineberg, 2000: 250).

In addition, our paper allows us to reflect upon the 1967 World’s Fair as an instrument of the U.S. nation branding. According to Ying Fan, nation branding “concerns applying branding and marketing communications techniques to promote a nation’s image” (2006: 6). Fan’s definition implies that nation branding is a special area of “place branding” that deals with national image promotion as its ultimate goal. Hlynur Gudjonsson shares Fan’s point of view and adds that governments are key initiators of nation branding. He writes that nation branding occurs “when a government or a private company uses its power to persuade whoever has the ability to change a nation’s image” (2005: 285). Keith Dinnie, in turn, argues that there is a line of distinction between a “national brand” and a “nation-brand”. If the former highlights that some products or phenomena can be regarded as a nation’s specificity that could make this nation unique in the international political environment, the latter confirms that a nation can be itself a brand, or a “unique, multidimensional blend of elements that provide the nation with culturally grounded differentiation and relevance for all of its target audiences” (2008: 15). Simon Anholt completes the current academic debate on the variety of definitions of nation branding by conceptualizing the term through marketing. He claims that nation branding is a kind of strategic self-presentation of a country with the aim to create “reputational” assets both at home and abroad through the promotion of this country’s national economic, political, and social interests. Anholt’s findings suggest that nation branding, state branding, and country branding are, in fact, two interchangeable terms (Anholt, 2007). By analyzing Warhol’s artwork through the lens of the Montreal Fair, we seek to explain why the U.S. government chose to display Warhol’s paintings as part of its official exhibition program and what benefits this synergy had for both the U.S. state and the artist himself.

Biosphere as the U.S. National Brand at the 1967 World’s Fair

The 1967 World’s Fair took place in Montreal, Canada, from 27 April to 29 October 1967. It was officially recognized by the BIE as a “universal and international exposition” (Galopin, 1997) and thus became the first Fair of such a kind to be ever set up in North America1. Originally, the 1967 World’s Fair was supposed to be held in the USSR to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution, but the Soviet government unexpectedly withdrew its request to host the Fair. Subsequently, in late 1962, the BIE decided to grant the right to host the 1967 World’s Fair in Canada to celebrate the country’s centennial year. With the support of Senator Mark Drouin of Québec, Montreal became a place serving as a focal point to organize the 1967 World’s Fair and highlight the international celebrations of Canada’s 100th birthday. In total, the Montreal Fair featured 62 national pavilions, 3 regional pavilions, and 268 private pavilions (Kretschmer, 1999: 302).

The U.S. National Pavilion, which still functions today as the Environment Museum, was called the Biosphere. It represented a geodesic dome elaborated by the architect Buckminster Fuller. The Pavilion’s futuristic architectural design fits very well into the Fair’s main theme “Man and his World” which derived from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s autobiographical novel Terre des Hommes. According to the official statement of the Canadian Corporation for the 1967 World Exposition, this theme was selected by a group of eminent scholars at the Montebello Conference in the Spring of 1963 with the aim to demonstrate “the behavior of man and his environment, his ideological, cultural and scientific achievements”2. The choice of this poetic theme invited the Fair’s participants to “unfold in different ways” the story of “man’s hopes, his aspirations, his ideas and his endeavour”3. Reflecting on this, the organizers conceptualized the Fair as “simultaneously one man’s environment and the gathering place of all men”, as “both the forum and market place” and “a place of meeting and exchange”4.

The U.S. participation in the Montreal Fair was efficient and versatile. As this expo received BIE’s highest status and was considered a hugely mediated global event, the U.S. government was particularly interested in using it for nation branding purposes and advancing the positive image of America abroad. Hence, it is not surprising that President Lyndon Johnson credited the United States Information Agency (USIA), a government body that united various government-sponsored efforts aimed at communicating directly with foreign publics for the purposes of informing and influencing, with putting together the program for the U.S. National Pavilion. Legendary diplomat Jack Masey was one of the crucial figures who stood behind the organization of U.S. participation in the 1967 World’s Fair. As head of design of the U.S. national exhibit, he was responsible for selecting the events and monitoring the activities to be shown in the Biosphere. Masey not only sought to display the U.S. national achievements around a particular topic but also tried to communicate efficiently these achievements to the international public. In his 1966 report “Creative America” which anticipated the demonstration of the U.S. national exhibit in Montreal, Masey described a visitor’s experience of coming to the Biosphere in the following terms:

Upon entering the United States Pavilion, the visitor will find himself in a transparent steel and plastic structure which soars 20 stories [sic] above him and which encloses a multi-level platform system interconnected by escalators and stair systems. He will at once be introduced to a series of new and sensory experiences much like the atmosphere of a Peronesi [sic] print5.

Masey’s comparison of the U.S. National Pavilion with the art of the Italian Renaissance artist Piranesi (although mistakenly spelled by Masey as Peronesi) is quite ambiguous. Most probably, Masey referred to Piranesi’s series of sixteen prints called Carceri d’Invenzione that depicted the fantastic labyrinthine aggregates of the monumental Roman architecture and ruins. On the one hand, such a comparison reflects the complex nature and the subtle design of Fuller’s Biosphere as an architectural object. On the other hand, however, the identification of the U.S. National Pavilion with carceri, or prison, may misinterpret the general meaning of the American exhibit and mistakenly associate it with a place of confinement. We tend to think that Masey did not take into consideration the second interpretation of Piranesi’s prints as embodiments of mental and physical captivity. In his report, he went on saying that the USIA had made a lot of efforts “to create an architecture and to devise an exhibit presentation noted for originality and daring so as to fully exploit the opportunity for experimentation”6. In such a way, Masey emphasized only the positive sociocultural side of the U.S. national exhibit to be shown in Montreal.

If Masey played the role of the conceptual designer, or bluntly speaking the “grey cardinal”, of the U.S. National Pavilion, other U.S. diplomats who also participated in the conception of Biosphere were appointed to the less ambitious positions. For instance, we could emphasize the outstanding role of the prominent diplomat John Slocum who assisted Masey in the early organization of the U.S. national exhibit in Montreal. As coordinator of planning, Slocum was responsible for giving momentum to the U.S. preparation for the Fair. From Slocum’s correspondence with the director of the transportation section of the 1964 World’s Fair Francis Miller we know that the U.S. government started to make plans about Montreal only in 1965, even though the BIE had announced the location of the next World’s Fair back in 1962. Slocum wrote to Miller on 3 December 1964:

There is very little that can be said about the status of U.S. participation in Montreal at the present time. We have selected an architect and an exhibit designer, but neither has as yet been announced7.

Apart from being concerned about the slow pace at which the U.S. preparation for the 1967 World’s Fair was advancing, Slocum also worried about the high costs of U.S. national participation in the Fair. The latter concern was addressed in the correspondence between USIA’s administrative director Ben Posner and USIA’s officer Sanford Marlowe. On 26 January 1965, Posner complained to Marlowe that, despite Slocum’s budgetary concerns, the estimated cost of U.S. participation in the Montreal Fair should be set at $12 million8. The U.S. Congress, however, was, like Slocum, quite skeptical about attributing a large sum of American taxpayers’ money to the international initiative that, according to the Congressmen, did not pursue clear foreign policy goals in contrast to military operations or economic programs. Therefore, Congress “earmarked” only $9,300,000 for U.S. participation in Montreal9. In contrast, the Canadian government spent $304,500,000 on the organization of the 1967 World’s Fair10, whereas the Soviet Union, according to Richard Strout of Christian Science Monitor, spent $17,000,000 on its national exhibit11.

Slocum’s mission as coordinator of planning ended on 17 March 1966, when the U.S. Senate confirmed President Johnson’s nomination of Stanley Tupper as commissioner general for the U.S. participation in the 1967 World’s Fair. Tupper had nothing to do with the U.S. diplomatic corps in general and the USIA in particular. Instead, he was a U.S. representative from Maine and had no professional background in international relations. Tupper’s position as commissioner general was rather nominal: he was supposed to monitor how the USIA was spending the money allocated by Congress on the preparation of the U.S. national exhibit for Montreal. On 18 March 1966, USIA’s director Leonard Marks issued a memorandum in which he urged all “element heads” of the USIA to “cooperate with the U.S. Commissioner General-designate and his staff”12. For Marks, cooperating with Tupper was a necessity rather than a desire. The approval of Tupper’s nomination by the executive and legislative branches of power allowed him to act as an intermediary between the institutions of the U.S. representative democracy and the alienated-from-the-ordinary-Americans diplomatic milieu. Marks did not regret Tupper’s involvement in the preparation of the American program for Montreal and noted that the 1967 World’s Fair was a good opportunity for the USIA to demonstrate to the American people the usefulness of this bureaucracy13.

American Painting Now as the Brand for “Creative America” at the 1967 World’s Fair

As both Marks and Tupper believed that the coordination of activities between USIA’s officers and Tupper’s team was crucial for the successful participation of the U.S. in the Montreal Fair, they decided to introduce a system of biannual reports to harmonize their work. Largely, Marks and Trupper published three progress reports reflecting intense collaboration between all institutions and interest groups responsible for designing the U.S. National Pavilion for the 1967 World’s Fair14. The first progress report of 30 December 1965, which was compiled by Slocum and his associates before Tupper’s official nomination, confirmed the choice of the Biosphere as an architectural space for the U.S. National Pavilion and the contents to be shown in it. It said that the U.S. participation in Montreal would concern itself with the “Creative America” topic suggested by Jack Masey and revealed that all supporting exhibits would “illustrate notable American accomplishments and breakthroughs in the arts, space and technology” and would be organized along the following thematic lines: Lunar Exhibit, Fine Arts Exhibit, New Technology Exhibit, American Heritage Exhibit, Creative America Film, and Special Events Theater15. The second progress report of 30 June 1966 introduced Tupper as commissioner general and announced USIA’s signing of the contract with George Fuller Company for the construction, fabrication, and installation of the Biosphere. According to the report, the cost of building the Biosphere amounted to $4,925,000, or almost half of the budget allocated by Congress for the U.S. participation in the Fair16. The third progress report of 31 December 1966 described the state of construction of the Biosphere and offered the first draft schedule of the events to be held in the Biosphere during the Fair. Among others, this report provided details about the Fine Arts Exhibit planned for the Fair. It introduced the would-be American Painting Now exhibition in the following way:

AMERICAN PAINTING NOW—This exhibit consists of a collection of contemporary paintings depicting new and experimental trends currently in evidence in American painting. This exhibit has been designed to fully exploit the height (20 stories [sic]) and volume (6,700,000 cubic feet) of the United States Pavilion. Huge dacron sailcloth “panels”, ranging in height from 20 to 90 feet, will form the backgrounds against which the paintings will be shown. There will be approximately 25 large-scale works of art on view (some as high as five stories [sic]) representing a variety of styles and techniques of the more significant contemporary American schools of painting17.

Despite its general tone, the draft of the American fine arts exhibit18 present in the third progress report reveals three important things. Firstly, it confirms that the overall idea of the U.S. fine arts exhibit for the 1967 World’s Fair was agreed upon already back in late 1966. Secondly, it tells us the name of the exhibition—American Painting Now. Otherwise, it sets the time frame (the contemporaneity) of the art to be shown. Thirdly, it informs us about the large scale of the exhibit in terms of the size of the artworks (panels instead of paintings) and of the gallery space of the exhibit. Nevertheless, the report does not specify the cost of the exhibit, the name of the curator of the show, and the artists and artworks selected.

The archival information reveals that the USIA did not prepare American Painting Now on its own. Instead, due to the lack of art professionals in this institution, the USIA signed a contract with the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston (ICA Boston) and its art curator Alan Solomon to develop the fine arts exhibit destined for the 1967 World’s Fair. The choice of Alan Solomon as curator of American Painting Now was not fortuitous. In fact, Solomon had already had previous experience staging successful international exhibitions under the auspices of the USIA. Most importantly, the USIA had commissioned Solomon, who had worked as a curator at the Jewish Museum in New York back then, to mount the Pop Art group exhibition shown in the American Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1964. Solomon’s exhibition produced a favorable impression on the international public and resulted in Robert Rauschenberg’s victory at the 1964 Venice Biennale.

In total, it took the USIA one year and a half to negotiate with Solomon the contents of the American Painting Now exhibition. In fact, the idea to recruit Solomon as curator of the fine arts exhibit for the 1967 World’s Fair belonged to Jack Masey who was satisfied with Solomon’s contribution to the American Pavilion at the 1964 Venice Biennale. The exchange of thoughts between Masey and Solomon about the prospects of showing contemporary American art in Montreal began in August 1965. On 9 August 1965, Masey wrote his first letter to Solomon in which he suggested that the latter should prepare the exhibition proposal taking into consideration the assumption that “something like 4,000 square feet” would be available to “the art exhibition within the United States Pavilion”19. Solomon wrote back to Masey on 12 August 1965 and said that he was impressed “by the sound of the project” and USIA’s enthusiasm for it20. “To figure expenses and salaries”21, however, Solomon asked Masey to give him more information about when the work on the project was supposed to move onto a more active phase. Prolific correspondence between Solomon and Masey’s team at the USIA continued throughout 1966 and 1967.

The most serious obstacle in the preparation of the American fine arts exhibition for the Montreal Fair was Solomon’s long-standing indecisiveness about the list of artists and artworks to be featured in the exhibition that was supposed to occupy the majority of the U.S. Pavilion. Despite many years of curatorial practice, Solomon had never dealt with an exhibition that required such an enormous gallery space. Due to the complex architectural design of the Biosphere, he could not come up with an ideal number of artists and artworks in his exhibition. Solomon hesitated about choosing either too many artists or too many artworks. That’s why it took him over a year to make a final decision about the contents of his show. On 4 January 1967, USIA officer Philip Rogers urged Solomon to submit the final exhibition plan as soon as possible so that the USIA could begin the installation of the exhibit properly on time. Rogers wrote: “It is very critical that we receive a list of the paintings by title, the artists and other information to be placed on the painting captions by January 15”22. Rogers explained that good timing was critical because the USIA could not hold up other contractors “without incurring additional costs and perhaps risking late delivery”23.

The result of Solomon’s work as curator of the show went beyond USIA’s expectations. Solomon summarized the composition and objectives of American Painting Now in a brochure-like catalogue that accompanied the art show at the 1967 World’s Fair. When commenting on the potential global cultural outreach of his exhibition, Solomon said one very striking thing:

[…] Given world conditions at present, 1967 was a year to soft sell America rather than to display muscle. […] The American Pavilion was deliberately spare. It did not overwhelm or numb one with the sheer volume of its contents. […] We don’t need to expose others to our power and our appliances: they already live with both. Consider, for example, the anguish with which the French, and the joy with which the Italians, are being culturally and economically Americanized. Apart from our space displays, which of course fascinated everyone, the exhibitions in the American Pavilion were conceived to show the more familiar, unpretentious side of our culture. […] Our contemporary art, which since the Second World War finds itself in a position of leadership, seems to illustrate the potential of our cultural resources24.

Solomon’s statement reflects his profound understanding of the phenomena of public diplomacy, soft power, and nation branding. In this respect, Solomon’s far-reaching cultural-political vision can be considered a unique skill for an art curator. It represents an ideal combination of art-historical and international political knowledge and its correct application in practice.

Whose Brand? Andy Warhol’s “Self-Portraits” at the 1967 World’s Fair

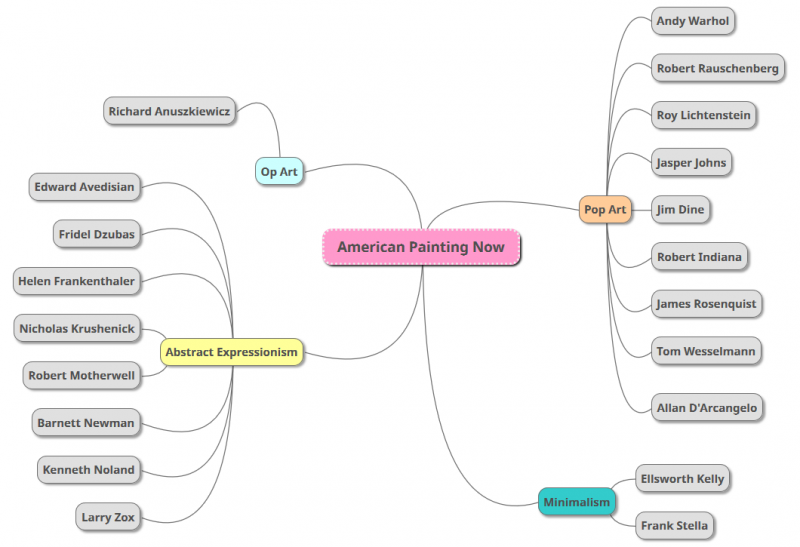

American Painting Now featured a few American artists representing different art movements of the 1950s and the 1960s. American Pop Art was only one of four contemporary American artistic tendencies present in the show, together with Abstract Expressionism, Op Art, and Minimalism. The following cognitive map demonstrates Solomon’s complex curatorial approach.

Figure 1: Artistic Movements Featured in American Painting Now.

Source: Author’s figure based on the data from Alan Solomon, American Painting Now, Boston, Institute of Contemporary Art, 1967, Alan R. Solomon Papers, 1907-1970, Bulk 1944-1970, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

As we can see, Andy Warhol was one of nine Pop artists displayed at American Painting Now. It is important to highlight that Solomon had curated the one-man show of Warhol’s work at the ICA Boston one year before the Montreal Fair, which had been, in fact, Warhol’s very first solo exhibition in a museum. Before 1966, Warhol’s one-man shows had been staged only in commercial art galleries. Since Solomon had been previously familiar with Warhol’s Pop Art, it is quite logical that he selected this artist for the American fine arts exhibit shown at the 1967 World’s Fair. It is worth mentioning, however, that Warhol was just one of nine Pop artists included in American Painting Now: he did not enjoy any specific treatment, nor was he granted any special conditions for his participation. Solomon loaned Warhol’s artworks through the artist’s art dealer Leo Castelli. Overall, it cost him $25,000 to loan from the Leo Castelli Gallery six Self-Portraits that Warhol created specifically for the Montreal Fair in March-April 196725.

Warhol’s Self-Portraits shown in Montreal represented six separate square silkscreened panels (acrylic and silkscreen on linen), 72x72 inches each (Frei and Printz, 2004: 256-257)26. Executed “in the frozen style of fixed-face presentation typical of his celebrity pictures”, they conveyed “little expressivity or intimations of subjectivity and inner life” (Freeland, 2010: 253) and paraded a “characteristic distance and refusal of any humanist depth of feeling” (James, 1991: 35). In the context of the Fair’s main theme (“Man and his World”), Solomon’s choice of Warhol’s artworks was rather radical. Instead of selecting some of Warhol’s artworks that bore on the broader socio-political issues of the era, Solomon chose to display Warhol’s personal brand as a separate subject matter. Self-Portraits emphasized only the first word of the Fair’s theme (“Man”) and completely omitted its remaining part (“World”). In this respect, Warhol’s artworks offered an alternative interpretation of the Fair’s theme. Instead of connecting “man” and “his world”, Self-Portraits juxtaposed these two terms. Otherwise speaking, Warhol’s artworks implicitly represented a critical approach to the Fair’s theme: they raised an issue of an ongoing conflict between man and his surrounding environment, hinted at the lack of unity among nations all over the world, and tackled the issue of integrity and strength of the inter-human connections.

The most accurate account of the significance of Self-Portraits for the American fine-art exhibit in Montreal was offered by the artist himself. As Warhol admitted, “I’m sure I’m going to look in the mirror and see nothing. People are always calling me a mirror and if a mirror looks into a mirror, what is there to see?” (Whiting, 1987: 70). In addition, Warhol wrote:

The Montreal Expo had opened in May on the banks of the St. Lawrence River with six of my Self-Portraits up there at the U.S. Pavilion, and I flew up to Canada with John de Menil and Fred in Mr. de Menil’s jet to see them. The American pavilion was Buckminster Fuller’s big geodesic dome, with its aluminium shades catching the sun, and an Apollo space capsule and a long free-span escalator. Those were things like you’d expect to find at an international exposition. What was unusual was that the rest of the American show was almost completely Pop—it was called Creative America. I remember thinking as I looked around it that there weren’t two separate societies in the United States anymore—one official and heavy and “meaningful” and the other frivolous and Pop. People used to pretend that the millions of rock-and-roll 45’s the kids bought every year somehow didn’t count, but that what an economist at Harvard or some other place like that said, did. So this U.S. exhibit was like an official acknowledgment that people would rather see media celebrities than anything else. In the way of art there were works by Rauschenberg and Stella and Poons and Zox and Motherwell and D’Arcangelo and Dine and Rosenquist and Johns and Oldenburg. But a lot of the show was pop culture itself—movies and blow-ups of stars, and props and folk art and American Indian art and Elvis Presley’s guitar and Joan Baez’s guitar. And these things weren’t just part of the exhibit; they were the exhibit—Pop America was America, completely (Warhol and Hackett, 1980).

Warhol’s quote reveals two curious facts about the artist’s participation in the 1967 World’s Fair. On the one hand, Warhol’s words can be interpreted as a manifesto of recognition of American Pop Art by the U.S. government. They demonstrate USIA’s willingness to include the art of the sixties in the government-sponsored international exhibitions together with the well-established Abstract Expressionist painting (Guilbaut, 1983). On the other hand, Warhol emphasizes the growing power of the mass media both in the U.S. and abroad. He acknowledges the fact that the media stars, and not the government institutions, are “the driving force behind the triumph of American art in the United States” (Dossin, 2015: 121).

Taking these two facts into consideration, Solomon’s choice of Self-Portraits for the Montreal Fair appears to be not that random. In fact, Warhol’s artworks reflect several major cultural trends of 1960s America. Firstly, Self-Portraits emphasize the changing attitude toward the phenomenon of popular culture in U.S. society. For art historian Diana Crane, Warhol’s works are “transitional”, as they contain some elements of protest directed toward the aesthetic tradition in form of satire and parody and attempt to “redefine the relationship between high culture and popular culture by revising conventions concerning subject matter and technique that had served to maintain the distinctions between them” (Crane, 1987: 71). Secondly, Self-Portraits reveal how the phenomenon of fame has affected the creation and perception of art. According to art historian Isabelle Graw, Warhol’s works embody a shift from the old star system to the emergence of new celebrity culture: if old stars “were admired on the basis of their performative achievements”, the attraction of contemporary celebrities “is based purely on personality and the way they supposedly live” (Graw, 2009: 172).

It is worth mentioning that even though six 72-inch Self-Portraits displayed in Montreal were painted by Warhol specifically for the 1967 World’s Fair, this genre had appeared in Warhol’s Pop Art much earlier. In Warhol’s words, the idea to draw self-portraits did not belong to him. It was Ivan Karp, associate director of the Leo Castelli Gallery, who suggested this idea to the artist. Warhol would later recall this moment: “I asked Ivan for ideas, too, and at a certain point he said, ‘You know, people want to see you. Your looks are responsible for a certain part of your fame—they feed the imagination.’ That’s how I came to do the first Self-Portraits” (Warhol and Hackett, 1980). Warhol created his first series of ten self-portraits back in 1964. The pictures were based on the photographs of Warhol staged in the neutral anonymous setting of a photo booth. The very first self-portrait was commissioned to Warhol by art collector Florence Barron. The circumstances pertaining to other self-portraits remain unknown. In 1966-1967, Warhol created his second series of self-portraits, all of which were commissioned by the Leo Castelli Gallery. These works announced a functional shift in Warhol’s art: they demonstrated the artist’s new take on color as a primary effect of serial repetition. To put it simply, serial repetition now served as a template for the display of color and not vice versa. The six Self-Portraits shown in Montreal belonged to Warhol’s second attempt at experimenting with the genre of self-portraiture, which would remain a recurrent topic in Warhol’s art till the artist’s death (De Diego Otero, 2007).

Conclusion

The inclusion of Andy Warhol’s Self-Portraits in the American fine-art exhibit at the 1967 World’s Fair was a win-win situation for both the U.S. government and the artist himself. Whereas the U.S. political establishment presented the nonconformity of the 1960s American Pop Art to the standards of the 1950s Abstract Expressionism as a novel national cultural-political brand, Warhol managed to turn his own image into a commercially successful personal brand. On 25 October 1967, Tupper’s Deputy Milton Fredman wrote a letter of appreciation to Warhol in which he thanked the artist for his contribution to American Painting Now. In Fredman’s opinion, the U.S. participation in the Fair “was an outstanding success” and Warhol’s Self-Portraits “played such an important part in that success”27. Furthermore, Fredman noticed:

The magnitude of your contribution to the success of the United States Pavilion cannot begin to be fully expressed in words alone. Your personal effort, enthusiasm and genuine interest in creating a work such as your SELF-PORTRAIT, 1967, especially for the AMERICAN PAINTING NOW exhibit, truly reflects not only the spirit which animated the United States Pavilion, but, even more important, the spirit which created and sustains the United States of America. No country can continue along the path of greatness without the nucleus of strength, integrity and creative expression which, in all ages, has been contained in and cherished by those few who are blessed with an artist’s perception and vision of life. You are, indeed, one of those rare individuals28.

Due to the missing archival information, we do not know if Warhol responded to Fredman’s letter or not. In any case, Fredman’s words confirm USIA’s deep gratitude for Warhol’s contribution to the 1967 World’s Fair, which is quite surprising in the context of the U.S. government’s long-standing neglect of American Pop Art. Otherwise speaking, Fredman’s letter reveals a gradual shift in the character of the U.S. government’s endorsement of postwar American art. It discloses the U.S. government’s acceptance of the cultural values of American Pop Art as the dominant cultural values of the American nation. However, as historian Laura Belmonte points out, the 1960s U.S. diplomatic corps, although using a multitude of informational and cultural instruments to communicate with foreign audiences, touched upon only some select American values. She writes:

U.S. information strategists presented the United States as a nation that valued freedom, tolerance, and individuality. They emphasized the egalitarian nature of the U.S. political system and the vibrancy of American culture. They extolled the U.S. standard of living and capitalism. While muting coverage of racism and economic inequalities, they offered a markedly liberal vision of America that promised progress and prosperity for individuals and families (Belmonte, 2008: 179).

Indeed, the issue of economic, gender or racial inequality was taboo for the whole U.S. diplomatic corps of the era (Krenn, 1999). The U.S. government saw the problem of socio-economic inequality as one of the greatest pitfalls of American democracy and thus excluded it from the official foreign policy agenda to avoid criticism at the international level. It is curious that although American Pop Art was the brightest American modern art movement, the U.S. government was reluctant to use it for nation-branding purposes because it falsely believed that Pop Art “may have been to the facts of economic and racial inequality in the United States” (Crow, 1996: 39). American Pop Art’s close standing to the sixties civil rights movements and underground cultures impeded the U.S. diplomatic actors from including this type of art in any of its international art shows for quite a long time.

With the inclusion of Self-Portraits in the 1967 World’s Fair, we can clearly see that by the late 1960s, Abstract Expressionism had ceased to be the only artistic movement used for U.S. nation branding purposes. However cautiously and marginally, Warhol’s Pop Art got finally included in the government-sponsored American international cultural-political agenda, which gradually opened the social and cultural issues previously held marginal or unacceptable. If the American art of the 1950s had shown social-political conformity, the American art of the 1960s was “a house divided” (Wagner, 2012). With the growth of “robust and varied dissent in cultural industries” that articulated “an alternative vision” of the American way of life, the U.S. government found it ever harder to “construct a uniform and sanitized national identity with rigid lines between the Soviet and American spheres” and, consequently, had nothing left but to diversify the cultural scope of its national political brand (Falk, 2010: 214). In fact, before the 1967 World’s Fair Warhol’s Pop Art had never appeared on the international scene under the patronage of some U.S. governmental institution. Therefore, the 1967 World’s Fair represents a crucial moment in the history of the global circulation of Warhol’s Pop Art under the auspices of American state-sponsored diplomatic institutions.

Besides the U.S. government, Warhol likewise benefited from participating in the 1967 World’s Fair. Self-portraits became closely associated with Warhol’s artist-brand. They now served as “a trademark that supported both Warhol’s artistic work and his media appearances” (Elger, 2004: 81), where the art product and the artist’s image were identical. As art historian Katherine Hoffman suggests, Warhol’s experiments with self-portraiture have contributed to the further development of this genre in twentieth-century American art. Talking about Pop artists’ self-portraits in general, Hoffman makes the following remark:

[…] Pop Art praised the elimination of the artist from the artwork or the reduction of the artist’s role as an interpreter of experience. Art and the cult of the artist were to be demystified. Advertising images were becoming almost more real than reality itself. Surfaces were more important, in some instances, than anything that might lie beneath them. Gone were the romantic “self” and any sense of passion and mood. Personal traits of the subject were to be removed. The reality of inner experience was to be denied. Here was a “minimal self” (Hoffman, 1996: 174).

Hoffman’s comparison of Pop self-portraits with Christopher Lasch’s idea of a “minimal self” shades more light on the significance of Warhol’s artworks for the Montreal Fair’s theme. In Lasch’s terms, Pop Art promulgates the power of consumption and mass culture that “make available to everybody an array of personal choices formerly restricted to the rich” (Lash, 1984: 34). This artistic movement stimulates individuals to make their own decisions and act on their own judgment and taste. A social system based on mass production, mass consumption, mass communications, and mass culture assimilates all social activities to the demands of the market place. Consequently, these developments bring about a new kind of personhood characterized “by some observers as self-seeking, hedonistic, competitive, and ‘antinomian’, by others as cooperative, ‘self-actualizing’, and enlightened” (Lash, 1984: 52). In this respect, Warhol’s Self-Portraits promote a “psycho-ecological point of view” on a post-industrialist society that insists on the cultural determinants of personality and the value of “transactions between the individual and his environment” (Lash, 1984: 54).

All in all, by turning the figure of an artist into a brand, Warhol captured the spirit of the American art scene of the sixties that introduced the cult of an artist-star (Beatrice, 2012) and imposed new standards on the aura of an artist (Dal Lago and Giordano, 2005). In the words of art historian Thomas Crow, in a “competitive fishbowl” of the American art market rapidly developing in the 1960s, “artists had to establish and maintain a dominating personal aura, that is, if dealers were to be successfully cultivated, critics cajoled or intimidated, and fascinated collectors convinced that supporting this art offered an entrée to flattering recognition and a share of the glamor for themselves” (1996: 144). Otherwise speaking, the sixties changed the social role of an artist as such. An artist turned from being an art creator to an art marketer or an art influencer. In Warhol’s opinion, an artist’s aura was synonymous with his monetary value in the art market. According to Warhol’s logic, which fully contradicted, for instance, the philosophy of Walter Benjamin who claimed that the aura is a quality that only exists outside of commodity production and technological reproduction (2008), an artist had a good aura if he was famous. Self-Portraits were an excellent means to add up to the artist’s fame and, consequently, his aura. As Warhol wrote in his Philosophy, “an artist should count up his pictures so you always know exactly what you’re worth, and you don’t get stuck thinking your product is you and your fame, and your aura” (Warhol, 1975).